Unlike virtually every other active device, the power MOSFET is unusual in that its schematic symbol includes a parasitic device – the body diode. The body diode is intrinsic to the device’s structure. It remains despite a number of fundamental changes in power MOSFET structure and device designs including the two most common types today — planar and trench devices.

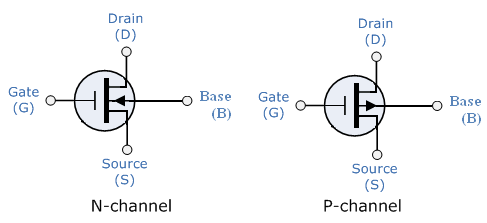

The Body Effect.doc 1/3 Jim Stiles The Univ. Of EECS The Body Effect In an integrated circuit using MOSFET devices, there can be thousands or millions of transistors. As a result, there are thousands or millions of MOSFET source terminals! But, there is only one Body. Body Effect. So far, we have been ignoring the substrate (or bulk or body) of the transistor and assumed that is it tied to the source. However, we cannot always make that assumption. – In integrated circuits, body is common to many MOS transistors and channel is connected to most negative (positive) supply for nMOS (pMOS) transistors. As we know that the threshold voltage is a function of the total charge in the depletion region (i.e. Thus as the body voltage V B drops then depletion charge (Q dep) increases which increases the threshold voltage (V TH). This effect is called as the body effect or back gate effect. The channel strength and the threshold voltage can be changed through application of appropriate voltage to the body terminal of the MOSFET. This is known as the body effect. For gate voltages less than threshold voltage, current drops off exponentially and as feature sizes decrease the way MOSFETs behave in this region becomes important. Body bias is the voltage at which the body terminal (4th terminal of mos) is connected. Body effect occurs when body or substrate of transistor is not biased at same level as that of source.

The presence of the body diode as an explicit element of the schematic symbol is an oddity. After all, we don’t pepper the MOSFET symbol with any of the three primary parasitic capacitances though they, too, affect the switch’s dynamic performance and, under suitable circuit conditions, lead to switching faults. But the body diode’s presence and behavior have become so much a part of the overall MOSFET device qualities that common circuit topologies depend on, or at least anticipate, the parametric performance of the parasitic component.

Discreet power MOSFETs also feature a parasitic bipolar transistor, but the metallization connecting the source and body regions — also an explicit feature of the schematic symbol — shorts the base-emitter junction. This prevents the bipolar device from turning on under all but the most extreme conditions. The remaining base-collector junction is in parallel with, and behaves essentially as part of, the body diode.

Many of the most common power MOSFET applications involve devices, in either half- or full-bridge configurations, driving inductive loads. Buck-converter topologies are a typical example. The high-side FET operates with a duty cycle D approximately equal to

When the high-side switch turns off, the inductor current has ramped to its peak for the given clock cycle. The controller will impose an amount of dead time between the high-side MOSFET turning off and the low-side device turning on to prevent shoot through (rail-to-rail conduction through the half bridge). Nonetheless, the inductor will try to maintain its current, pulling the switching node negative until the low-side MOSFET’s body diode conducts. Even after the low-side switch turns on, the body diode doesn’t turn off for a period trr, the reverse recovery time, during which charges within the PN device must recombine.

Two parts of the MOSFET’s loss model are associated with the body diode in this scenario. The first is an IL∙VD term during the diode’s conduction interval. This is significantly larger than the switch’s I2∙RDS(on) loss — one motivation to minimize the switching dead time. The second is the recombination current, which adds to the inductor current flowing through the switch’s RDS(on). This results in slightly higher I2R losses than the circuit’s external behavior would suggest and a correspondingly higher operating temperature for the switch. Because RDS(on) exhibits a positive TCR (temperature coefficient of resistance), the device dissipation rises further, beyond that which constant-temperature calculations would predict.

Should the switching dynamics and thermal performance fall short of your circuit’s requirements, or if you’re designing for maximum energy efficiency, you can essentially eliminate the body diode’s contribution to the switch’s behavior. A Schottky diode connected in parallel to the body diode will conduct with a lower forward voltage, preventing the body PN junction from becoming forward biased. The Schottky diode is a majority-carrier device and exhibits no recombination. Be sure to use short, wide traces to connect the Schottky and the MOSFET. Even small stray inductances can reduce the Schottky diode’s effectiveness.

The threshold voltage, commonly abbreviated as Vth, of a field-effect transistor (FET) is the minimum gate-to-source voltage VGS (th) that is needed to create a conducting path between the source and drain terminals. It is an important scaling factor to maintain power efficiency.

When referring to a junction field-effect transistor (JFET), the threshold voltage is often called pinch-off voltage instead.[1][2] This is somewhat confusing since pinch off applied to insulated-gate field-effect transistor (IGFET) refers to the channel pinching that leads to current saturation behaviour under high source–drain bias, even though the current is never off. Unlike pinch off, the term threshold voltage is unambiguous and refers to the same concept in any field-effect transistor.

Basic principles[edit]

In n-channelenhancement-mode devices, a conductive channel does not exist naturally within the transistor, and a positive gate-to-source voltage is necessary to create one such. The positive voltage attracts free-floating electrons within the body towards the gate, forming a conductive channel. But first, enough electrons must be attracted near the gate to counter the dopant ions added to the body of the FET; this forms a region with no mobile carriers called a depletion region, and the voltage at which this occurs is the threshold voltage of the FET. Further gate-to-source voltage increase will attract even more electrons towards the gate which are able to create a conductive channel from source to drain; this process is called inversion. The reverse is true for the p-channel 'enhancement-mode' MOS transistor. When VGS = 0 the device is “OFF” and the channel is open / non-conducting. The application of a negative (-ve) gate voltage to the p-type 'enhancement-mode' MOSFET enhances the channels conductivity turning it “ON”.

In contrast, n-channel depletion-mode devices have a conductive channel naturally existing within the transistor. Accordingly, the term threshold voltage does not readily apply to turning such devices on, but is used instead to denote the voltage level at which the channel is wide enough to allow electrons to flow easily. This ease-of-flow threshold also applies to p-channeldepletion-mode devices, in which a negative voltage from gate to body/source creates a depletion layer by forcing the positively charged holes away from the gate-insulator/semiconductor interface, leaving exposed a carrier-free region of immobile, negatively charged acceptor ions.

For the n-channel depletion MOS transistor, a negative gate-source voltage, -VGS will deplete (hence its name) the conductive channel of its free electrons switching the transistor “OFF”. Likewise for a p-channel 'depletion-mode' MOS transistor a positive gate-source voltage, +VGS will deplete the channel of its free holes turning it “OFF”.

In wide planar transistors the threshold voltage is essentially independent of the drain–source voltage and is therefore a well defined characteristic, however it is less clear in modern nanometer-sized MOSFETs due to drain-induced barrier lowering.

Bulk Charge Effect

In the figures, the source (left side) and drain (right side) are labeled n+ to indicate heavily doped (blue) n-regions. The depletion layer dopant is labeled NA− to indicate that the ions in the (pink) depletion layer are negatively charged and there are very few holes. In the (red) bulk the number of holes p = NA making the bulk charge neutral.

If the gate voltage is below the threshold voltage (left figure), the 'enhancement-mode' transistor is turned off and ideally there is no current from the drain to the source of the transistor. In fact, there is a current even for gate biases below the threshold (subthreshold leakage) current, although it is small and varies exponentially with gate bias.

If the gate voltage is above the threshold voltage (right figure), the 'enhancement-mode' transistor is turned on, due to there being many electrons in the channel at the oxide-silicon interface, creating a low-resistance channel where charge can flow from drain to source. For voltages significantly above the threshold, this situation is called strong inversion. The channel is tapered when VD > 0 because the voltage drop due to the current in the resistive channel reduces the oxide field supporting the channel as the drain is approached.

Body effect[edit]

The body effect is the change in the threshold voltage by an amount approximately equal to the change in the source-bulk voltage, , because the body influences the threshold voltage (when it is not tied to the source). It can be thought of as a second gate, and is sometimes referred to as the back gate,and accordingly the body effect is sometimes called the back-gate effect.[3]

For an enhancement-mode nMOS MOSFET, the body effect upon threshold voltage is computed according to the Shichman–Hodges model,[4] which is accurate for older process nodes,[clarification needed] using the following equation:

What Is Body Effect In Mosfet

where is the threshold voltage when substrate bias is present, is the source-to-body substrate bias, is the surface potential, and is threshold voltage for zero substrate bias, is the body effect parameter, is oxide thickness, is oxide permittivity, is the permittivity of silicon, is a doping concentration, is elementary charge.

Dependence on oxide thickness[edit]

In a given technology node, such as the 90-nm CMOS process, the threshold voltage depends on the choice of oxide and on oxide thickness. Using the body formulas above, is directly proportional to , and , which is the parameter for oxide thickness.

Thus, the thinner the oxide thickness, the lower the threshold voltage. Although this may seem to be an improvement, it is not without cost; because the thinner the oxide thickness, the higher the subthreshold leakage current through the device will be. Consequently, the design specification for 90-nm gate-oxide thickness was set at 1 nm to control the leakage current.[5] This kind of tunneling, called Fowler-Nordheim Tunneling.[6]

where and are constants and is the electric field across the gate oxide.

Before scaling the design features down to 90 nm, a dual-oxide approach for creating the oxide thickness was a common solution to this issue. With a 90 nm process technology, a triple-oxide approach has been adopted in some cases.[7] One standard thin oxide is used for most transistors, another for I/O driver cells, and a third for memory-and-pass transistor cells. These differences are based purely on the characteristics of oxide thickness on threshold voltage of CMOS technologies.

Temperature dependence[edit]

As with the case of oxide thickness affecting threshold voltage, temperature has an effect on the threshold voltage of a CMOS device. Expanding on part of the equation in the body effect section

where is half the contact potential, is Boltzmann's constant, is temperature, is the elementary charge, is a doping parameter and is the intrinsic doping parameter for the substrate.

We see that the surface potential has a direct relationship with the temperature. Looking above, that the threshold voltage does not have a direct relationship but is not independent of the effects. This variation is typically between −4 mV/K and −2 mV/K depending on doping level.[8] For a change of 30 °C this results in significant variation from the 500 mV design parameter commonly used for the 90-nm technology node.

Dependence on random dopant fluctuation[edit]

Random dopant fluctuation (RDF) is a form of process variation resulting from variation in the implanted impurity concentration. In MOSFET transistors, RDF in the channel region can alter the transistor's properties, especially threshold voltage. In newer process technologies RDF has a larger effect because the total number of dopants is fewer.[9]

Research works are being carried out in order to suppress the dopant fluctuation which leads to the variation of threshold voltage between devices undergoing same manufacturing process.[10]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^'Junction Field Effect Transistor (JFET)'(PDF). ETEE3212 Lecture Notes.

This is called the threshold, or pinch-off, voltage and occurs at vGS=VGS(OFF).

- ^Sedra, Adel S.; Smith, Kenneth C. '5.11 THE JUNCTION FIELD-EFFECT TRANSISTOR (JFET)'(PDF). Microelectronic Circuits.

For JFETs the threshold voltage is called the pinch-off voltage and is denoted VP.

- ^Marco Delaurenti, PhD dissertation, Design and optimization techniques of high-speed VLSI circuits (1999))Archived 2014-11-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^NanoDotTek Report NDT14-08-2007, 12 August 2007

- ^Sugii, Watanabe and Sugatani. Transistor Design for 90-nm Generation and Beyond. (2002)

- ^S. M. Sze, Physics of Semiconductor Devices, Second Edition, New York: Wiley and Sons, 1981, pp. 496–504.

- ^Anil Telikepalli, Xilinx Inc, Power considerations in designing with 90 nm FPGAs (2005))[1]

- ^Weste and Eshraghian, Principles of CMOS VLSI Design : a systems perspective, Second Edition, (1993) pp.48 ISBN0-201-53376-6

- ^Asenov, A. Huang,Random dopant induced threshold voltage lowering and fluctuations in sub-0.1 μm MOSFET's: A 3-D “atomistic” simulation study, Electron Devices, IEEE Transactions, 45 , Issue: 12

- ^Asenov, A. Huang,Suppression of random dopant-induced threshold voltage fluctuations in sub-0.1-μm MOSFET's with epitaxial and δ-doped channels, Electron Devices, IEEE Transactions, 46, Issue: 8

External links[edit]

- Online lecture on: Threshold Voltage and MOSFET Capacitances by Dr. Lundstrom